| Header | Text |

| Overview | This page provides a general summary of spinal deformity, a quick glossary of related terms, and common signs and symptoms, diagnostic tests, and treatment considerations.

The Spine Hospital at The Neurological Institute of New York is recognized around the world as a leader in the treatment of spinal deformity.

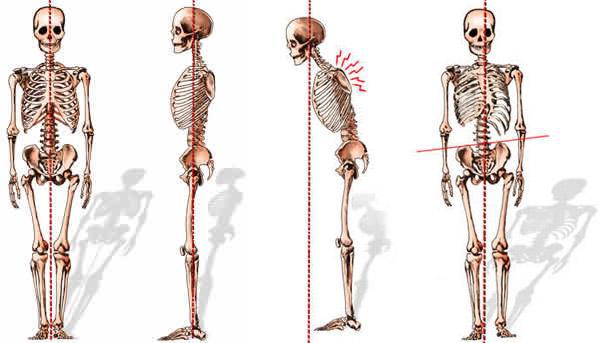

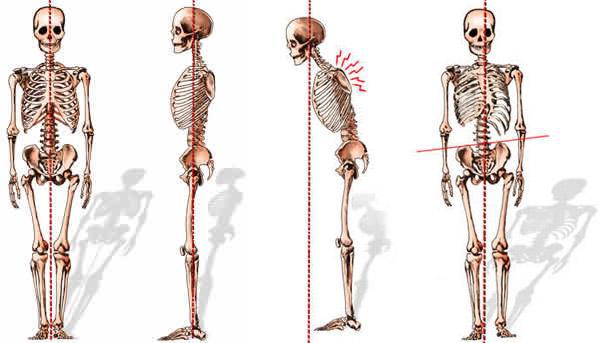

The normal spine is structurally balanced for optimal flexibility and support of the body’s weight. When viewed from the side, it has three gentle curves. The lumbar (lower) spine has an inward curve called lordosis. The thoracic (middle) spine has an outward curve called kyphosis. The cervical spine (spine in the neck) also has a lordosis. These curves work in harmony to keep the body’s center of gravity aligned over the hips and pelvis. When viewed from behind, the normal spine is straight.

Abnormal curvature in the spine can put it out of alignment. Abnormal curvature seen from the side is called sagittal imbalance. Types of sagittal imbalance include kyphosis, flatback syndrome, and chin-on-chest syndrome. Abnormal curvature of the spine seen from the back is called scoliosis.

Each of these conditions can arise for a variety of reasons, including congenital deformity (deformity present at birth), age-related degeneration, disease processes like tumors or infections, other conditions, or idiopathic causes (causes that are not yet understood).

|

| Glossary |

- Cervical: having to do with the spine in the neck. The normal cervical spine has a lordosis (inward curve)

- Thoracic: having to do with the spine in the upper and mid-back. The normal thoracic spine has a kyphosis (outward curve)

- Lumbar: having to do with the spine in the lower back. The normal lumbar spine has a lordosis (inward curve)

- Congenital: present at birth

- Degenerative: having to do with age-related wear-and-tear

- Idiopathic: arising for unknown reasons

- Sagittal deformity

- Kyphosis: spinal deformity in which the spine curves excessively outward, creating the appearance of a hunchback. Occasionally called hyperkyphosis, to differentiate it from the normal kyphosis of the thoracic spine.

- Chin on chest syndrome: cervical and upper thoracic kyphosis that is so severe the chin drops to the chest. Also referred to as dropped head syndrome or head ptosis.

- Lordosis: a rare spinal deformity in which the lower back curves excessively inward. Occasionally called hyperlordosis to differentiate it from the normal lordosis of the lumbar spine. Hyperlordosis may occur to compensate for hyperkyphosis elsewhere.

- Flatback syndrome: spinal deformity in which the lumbar spine loses its normal lordosis.

If deformities in the sagittal plane prevent the individual from achieving an upright posture with the head aligned over the hips, the result is sagittal imbalance.

- Scoliosis: a side-to-side curve in the spine. Classifications include

- Congenital: a form of scoliosis present at birth

- Infantile: scoliosis that occurs in patients 0-3 years old

- Juvenile: scoliosis that occurs in patients 4-10 years old

- Adolescent: scoliosis that occurs in patients 11-18 years old

- Adult: adult scoliosis may be idiopathic or degenerative in cause

|

| Signs and Symptoms | Signs are observable indications of a condition. Signs can be seen or felt by people other than the patient. Signs of scoliosis may include a difference in shoulder or hip height, a difference in the way the arms hang beside the body, a spine that is visibly off-center, or a head that appears off-center with the body. Signs of sagittal imbalance may include a stooped forward posture, a hump in the back, or an inability to stand up straight.

Symptoms can be felt by the person with the condition. Symptoms of scoliosis vary: most cases of infantile, juvenile and adolescent scoliosis, for example, produce no symptoms. Degenerative scoliosis is often accompanied by pain. Symptoms of sagittal imbalance range from mild discomfort to severe pain. Spinal deformities also have the capacity to interfere with the spinal cord or nerve roots. Stretch or compression of the spinal cord or nerve roots produces symptoms that may include pain, weakness, numbness, or tingling that travel down an arm or a leg.

|

| Tests and Diagnosis | To establish the existence and extent of spinal deformity, the following tests may be useful:

- X-ray (also known as plain films) –test that uses invisible electromagnetic energy beams (X-rays) to produce images of bones. Soft tissue structures such as the spinal cord, spinal nerves, the disc and ligaments are usually not seen on X-rays, nor on most tumors, vascular malformations, or cysts. X-rays provide an overall assessment of the bone anatomy as well as the curvature and alignment of the vertebral column. Spinal dislocation or slippage (also known as spondylolisthesis), kyphosis, scoliosis, as well as local and overall spine balance can be assessed with X-rays. Specific bony abnormalities such as bone spurs, disc space narrowing, vertebral body fracture, collapse or erosion can also be identified on plain film X-rays. Dynamic, or flexion/extension X-rays (X-rays that show the spine in motion) may be obtained to see if there is any abnormal or excessive movement or instability in the spine at the affected levels.

- Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging: uses a magnet and radio waves to provide detailed images of the spine as well as the spinal cord, the spinal nerves, and other soft tissues

- Computed tomography (CT) scan: a diagnostic imaging procedure that uses a combination of X-rays and computer technology to produce detailed images of bones and soft tissues. CT scans are more detailed than general X-rays.

|

| Treatments | For the most part, nonoperative treatments are recommended before surgery is considered. Nonoperative treatments include pain medications, physical therapy (including gait and posture training), and certain braces.

Surgery is considered if:

- The patient experiences severe pain that is not relieved by physical therapy, bracing, and/or pain medications

- The spinal deformity is progressing

- The condition has caused a physical deformity that is unbearable to the patient

- The condition has caused compression of the spinal cord or nerve roots

- The deformity has resulted from fractures, usually caused by osteoporosis

- The deformity is of such a magnitude that it is likely to progress even once skeletal growth is complete

The goals of surgery are to relieve symptoms and to align and stabilize the spine. However, since spinal deformity varies from patient to patient, no two surgical treatments will be the same. Our experienced surgeons can determine the best treatment for each patient and each situation.

Aligning and stabilizing the spine are complex procedures. Spinal alignment must be achieved from all angles, and keeping the spine in its stable position often requires implanting hardware such as screws and rods. Read more about deformity correction and stabilization here.

If the deformity has resulted in compression of the spinal cord or spinal nerves, the surgeon may perform a decompression surgery. A laminectomy is one common type of decompression surgery. In this procedure, the surgeon removes a section of bone called the lamina at the back of the vertebra. Removing the lamina provides extra space for the spinal cord and allows it to function properly.

For a detailed explanation of surgical procedures that may be required to treat a specific spinal deformity, refer to that condition’s individual page.

|

| Drs. Paul C. McCormick, Peter D. Angevine, Christopher E. Mandigo, Patrick C. Reid and Richard C.E. Anderson (Pediatric) are experts in treating spinal deformities. Each can also offer you a second opinion.

|