Football was a great love of Dr. Paul C. McCormick’s early life. As a boy being coached by his dad, as a teen weighing football scholarships and as a young man captaining Columbia’s team, McCormick reveled in the game.

Football was a great love of Dr. Paul C. McCormick’s early life. As a boy being coached by his dad, as a teen weighing football scholarships and as a young man captaining Columbia’s team, McCormick reveled in the game.

But so often a game is not “only a game,” and football wasn’t only a game for McCormick. Football was also a proving ground on which he could practice dedication and discipline in service of a greater goal.

Football allowed him to form close relationships with inspiring mentors whose lessons in leadership he would “pay forward” in years to come. And football even brought him to the great loves of his adult life, his family and his work as a neurosurgeon. Because it was football that brought him to Columbia University.

Dr. McCormick thanks Columbia football coach Bill Campbell for that. Campbell would go on to become CEO of Intuit, and eventually president of the Columbia Board of Trustees. But decades ago, as a first-year coach of Columbia’s football team, Campbell was facing a tough road. Columbia’s team hadn’t had a winning season in years. Campbell was looking for a gifted player who could help the team play its best, and he believed he had found that player in high school senior Paul McCormick.

For his part, the young McCormick was weighing offers from several schools, including big-name “football schools.” But Campbell’s approach struck a chord. At Columbia, Campbell pointed out, McCormick could make a real difference on a struggling team while also getting the best possible preparation for medical school. (McCormick had decided in eighth grade that he wanted to be a doctor.)

And then there was Coach Campbell’s charismatic, caring manner. McCormick’s instinct was that Campbell would be a great mentor. McCormick signed on at Columbia. The decision was momentous. “That was in 1974,” he says. “And I’ve been here ever since.”

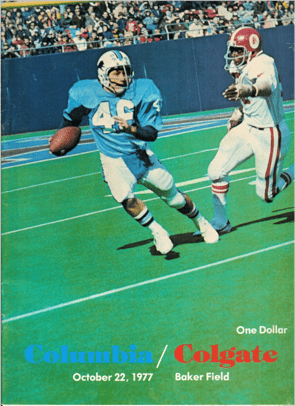

Columbia’s football team benefited from McCormick’s presence, and McCormick benefited from the Division I team’s lessons in teamwork and mentorship. Campbell recalls one game where he was forced by circumstance to fulfill McCormick’s wish of playing the entire game, instead of rotating play with the team’s other two running backs. McCormick played extremely well.

“We won the game,” says Campbell. “It was a wonderful win. Paul couldn’t walk on Sunday. He couldn’t walk on Monday. He couldn’t practice on Tuesday or Wednesday. We were lucky that [he was able to play the following week]. I think after that, he realized that it was pretty good to rotate.”

It was a lesson about teamwork that McCormick took to heart. Playing on Campbell’s team, he says, meant that “you were going to wear the Columbia uniform, you were going to be part of something greater than yourself, greater than any individual accomplishment.” It is an attitude McCormick has carried with him ever since. At the same time, “Paul was a phenomenal leader,” recalls Campbell. “He was a great mentor to a lot of the young people who came into the program [after him].”

McCormick played four years of football, captaining the team his senior year. He also played baseball for Columbia, completed his pre-med coursework and earned a degree in English.

When he was accepted to Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, McCormick wasn’t sure what kind of medicine he might like to study. A course on the nervous system helped him discover the answer.

“Everybody’s human nervous system is structurally very similar—but it can develop, evolve and change over a lifetime,” he says. “To me, that is just a cool concept.” As the course continued, he found neuroscience more than just cool.

He was deeply, truly fascinated by the nervous system’s complexity and its order. “In the nervous system,” says Dr. McCormick, “I experienced a wonder and a mystery. There’s a complexity to the central nervous system that defies comprehension, but there’s also a compelling logic, an elegant order to it. So that’s what was alluring and seductive about the neurosciences.”

At first, McCormick thought he might go into neurology. But when he spent time in the neurology department, the specialty didn’t “click” with him. “At the time, neurologists would just assess. They couldn’t interact, they couldn’t treat.” Disappointed, he decided to look into neurosurgery.

At that time, medical students thinking about a career in neurosurgery just had to find out about the discipline on their own. McCormick simply arranged to spend a week in the department, planning to use his initiative to learn whatever he could about working as a neurosurgeon. But a chance encounter changed that plan.

“I was on an elevator, I think the second day of my week on neurosurgery,” says Dr. McCormick. A neurosurgeon named Jost Michelsen got on the elevator, glanced at McCormick’s name tag and then took a longer second look. “He said, ‘Paul McCormick? You were the captain of Columbia’s football team, weren’t you?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘What are you doing here?’ I said, ‘Well, I’m doing a week on neurosurgery.’ He said, ‘Who are you doing it with?’ I said, ’Nobody, I’m just here.’ He goes, ‘Well, you’re with me now.’ I went to his office, [observed his surgeries] in the operating room, and he was very welcoming. I thought, ‘This guy’s a real role model.’”

That week with Dr. Michelsen cemented McCormick’s interest in neurosurgery. He was attracted to the demanding, exacting work and to the benefit it could provide people. “The seriousness of the conditions, the rapidity with which the patients could change and the profound consequences—to me, it all demanded a focus and commitment that was very appealing,” says Dr. McCormick.

Neurosurgery was the discipline for him. He could feel it. “When you know, you know,” he says. “Like when you meet the right girl or right guy, you know it.” McCormick had found the first love of his adult life.

And he was about to find the second.

After medical school, Dr. McCormick applied and was accepted to the neurosurgery training program at Columbia. During his internship in the general surgery ward, he met a registered nurse named Doris. And, well—“When you know, you know.” Two years after they met, the couple got married. And more than three decades later, “she’s the reason I get up in the morning,” Dr. McCormick says. “She’s the reward at the end of the day.”

As his family life and career began, the ideals of teamwork and mentorship that Dr. McCormick had learned from football became more and more important. The department director, Dr. Bennet M. Stein, was building a team-like neurosurgery department, and he saw that Dr. McCormick would be an ideal fit.

In Dr. Stein’s vision, each neurosurgeon would play a specialized role in the larger department. The setup is common now, but in the early eighties, it was groundbreaking. That was the tail end of the era when, Dr. McCormick says, “the really good neurosurgeons did everything.” The field was advancing quickly though. Dr. Stein saw that to build an outstanding department, he couldn’t hire individual neurosurgeons who all wanted to, as it were, play the entire game.

Instead, he sought highly talented surgeons who could cooperate and sub-specialize, each filling specific roles on the team. This would be the best way to provide excellent care to their patients. Dr. McCormick would be the spine specialist.

But first came a challenging year for Dr. McCormick’s “home” team. He and his wife had had their first child, Paul Jr. But Paul Jr. was still just a baby when it came time for Dr. McCormick to complete his sub-specialization through an intensive, year-long spine fellowship in Wisconsin. Dr. Stein had arranged the fellowship so that Dr. McCormick would receive the most thorough, well-rounded spine training, learning approaches and techniques from different experts in a different region of the country.

The McCormicks decided that it didn’t make sense to uproot Doris and the baby, moving them for only a short time to a strange city where they knew no one. Instead, Doris and Paul Jr. stayed near family in the New York area. Dr. McCormick did his fellowship in Wisconsin, flying back to New York to see his family only every couple of weeks. It was a tough year for everyone.

Finally, at the end of that year, Dr. McCormick had completed his spine training, and the home team was reunited for good. And its roster eventually grew. Paul Jr. was followed a few years later by Kyle, and a few years after that came Kaleigh.

Dr. McCormick began work at the Neurological Institute in 1990. With his superb training, his incredible surgical skill and the focus and dedication that had initially attracted him to the field, he was on his way to becoming the world-renowned spine surgeon he is today. In the early nineties, he established The Spine Hospital at the Neurological Institute of New York (formerly The Spine Center). He wanted it to be a place where the best spine specialists would work collaboratively—not just outstanding surgeons, but physical therapists, neurosurgery nurses, specialists in pain management and other practitioners. He was building a team of his own.

And he does see the center as a team, as something “greater than himself”—just as he did when he wore Columbia’s blue team uniform. He carefully grew The Spine Hospital at the Neurological Institute of New York, adding talented new surgeons and other specialists when the time was right. He has the highest praise for the other surgeons in the Spine Hospital and feels grateful that some of them now consider him a mentor. “It’s really a great honor and responsibility to be viewed as somebody’s mentor,” he says. “They choose you. You don’t choose them.”

As he worked to establish The Spine Hospital at the Neurological Institute, Dr. McCormick realized that he wanted a greater understanding of the “big picture” of medicine. So—while maintaining his clinical practice, establishing the Spine Hospital, being a father to three school-age children and also chairing the scientific section of a national neurosurgical organization—he enrolled in a two-year program for a Master’s in Public Health. University

He gained a greater understanding of medicine in society, of medical administration and finance, and of the best ways to measure patient outcomes—and again he graduated top of his class.

Dr. McCormick sees a gentle irony in his older children’s choices. “I was very close to my dad [who was a lawyer], but I didn’t want to do what he did,” he says. “I wanted to be my own person. Kids are interesting though. I try to tell my kids, ‘Look, don’t go into medicine because you think that’s what we want. We want you to be happy.’” Part of the “honor and responsibility” of being his children’s mentor was giving them the freedom to think for themselves and to pursue their own passions, medical or not.

Dr. McCormick’s children are nearly all grown. He has become a recognized expert in spine surgery, he leads The Spine Hospital at the Neurological Institute and he has already held the scientific chair and president’s seat in national neurosurgical organizations. But he’s not worried about where to go from here. Instead, he’s happy that up-and-coming neurosurgeons are becoming experts and stepping into leadership roles. “It’s about continuous renewal,” he says. “It’s about letting other people have a chance to develop. That’s what leadership is all about.”

“My greatest joy now is just to be a neurosurgeon,” he says. “To not worry about the political issues or administrative issues, but to just be the best neurosurgeon I can be. We do a long, arduous operation, and at the end of the day there’s a sense of accomplishment. A sense that you’ve done something, you’ve made a difference, in a way that not a lot of people can. To me, that’s the greatest reward.”

“My greatest joy now is just to be a neurosurgeon,” he says. “To not worry about the political issues or administrative issues, but to just be the best neurosurgeon I can be. We do a long, arduous operation, and at the end of the day there’s a sense of accomplishment. A sense that you’ve done something, you’ve made a difference, in a way that not a lot of people can. To me, that’s the greatest reward.”

Learn more about Dr. Paul McCormick on his bio page here.

Images courtesy of Dr. Paul McCormick